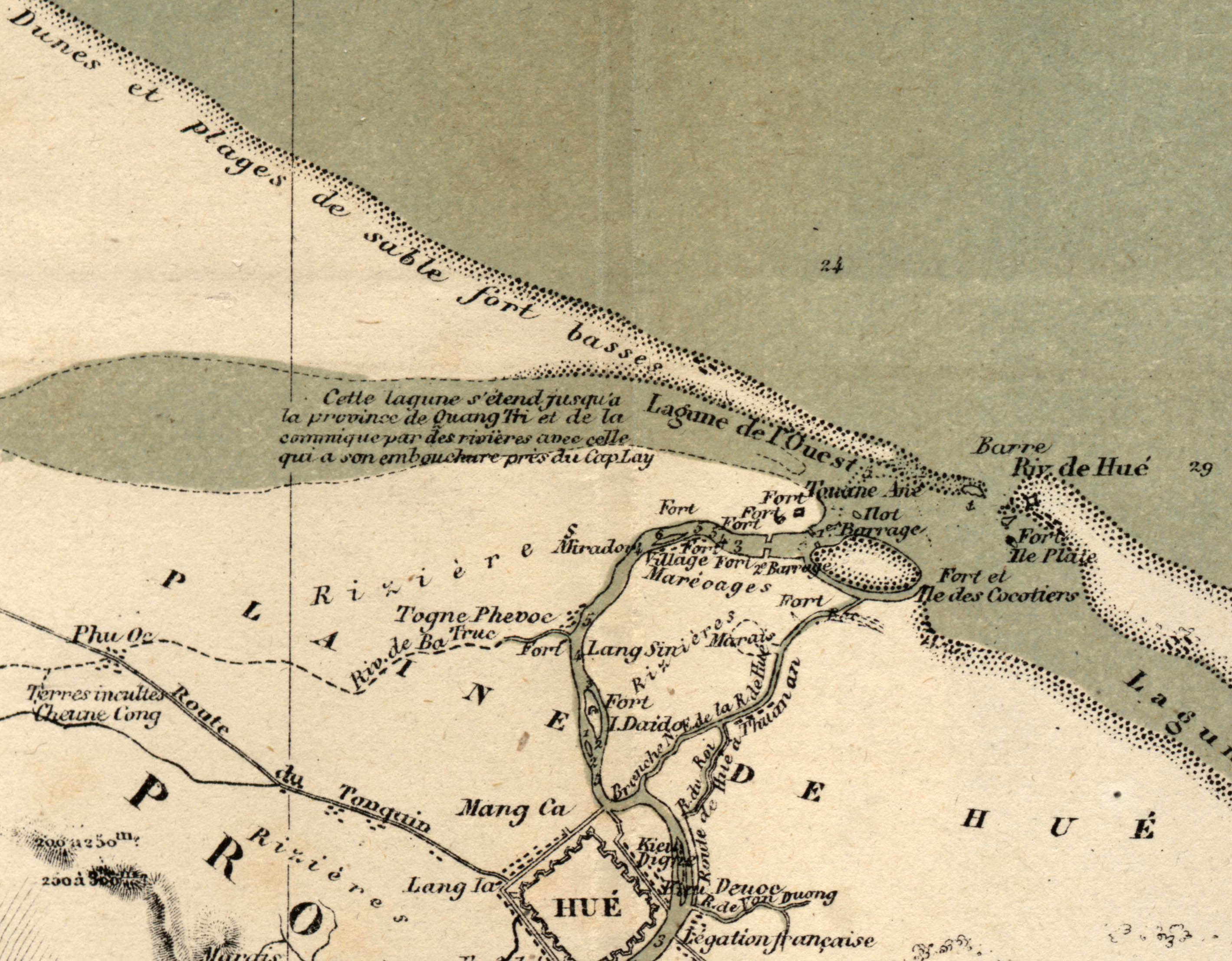

This first map contribution is one of my all-time favorites for the artistry of the cartographer and the story associated with it. In 1876, the government of the Third Republic made a sort of peace offering with the emperor of Đại Nam (Annam, Vietnam) in Huế, Tự Đức. The offering consisted of three older, slightly out-of-date warships. The official purpose was to help the struggling Vietnamese kingdom re-establish a small fleet since French ships had devastated Vietnamese naval ships in the conquest of Sài Gòn (1862) and the Lower Mekong (1867). The emperor had also given France port space in present-day Đà Nẵng and Hà Nội. So the French government sent three naval captains on a joint military training mission with Vietnamese sailors and officers. Of course, a hidden agenda was to survey the hard-to-access imperial capital, note the defensive landscape and provide any other details that might be helpful should France need, in the future (1883-84 to be exact) to invade. Enter Jules Léon Dutreuil du Rhins, amateur cartographer and troubled naval captain, age 30.

Dutreuil du Rhins was one of a cohort of adventurous, mapmaking Europeans who set out to fulfill his government’s diplomatic and surveillance initiatives while also collecting personal anecdotes sufficient to launch himself through travel books and speaking events as a celebrity adventurer. Like many of his adventurer colleagues, however, Dutreuil du Rhins died young at 48, killed when Golog peoples in southeastern Tibet attacked his survey mission. His last survey mission was published by others, and for the most part his reputation as a cartographer and adventurer faded.

When I encountered his Le royaume d’Annam et Annamites; journal de voyage, (Paris: E. Plon, 1879), I was immediately fascinated by his up-close-and-personal look at life in the beleaguered, war-ravaged imperial capital. The Nguyễn Emperor Minh Mạng had in by the 1830s pretty much banished most Europeans from the capital just as he put the finishing touches on a new Imperial City looking much like the Ming Dynasty city in Beijing. Forty years and several naval battles with France later, the monarchy was eager to get the new vessels and it seemed like maybe there was a possibility for co-existence, at least in the ancient, densely populated Vietnamese coastline stretching from Huế north to Hà Nội.

(Full res version)

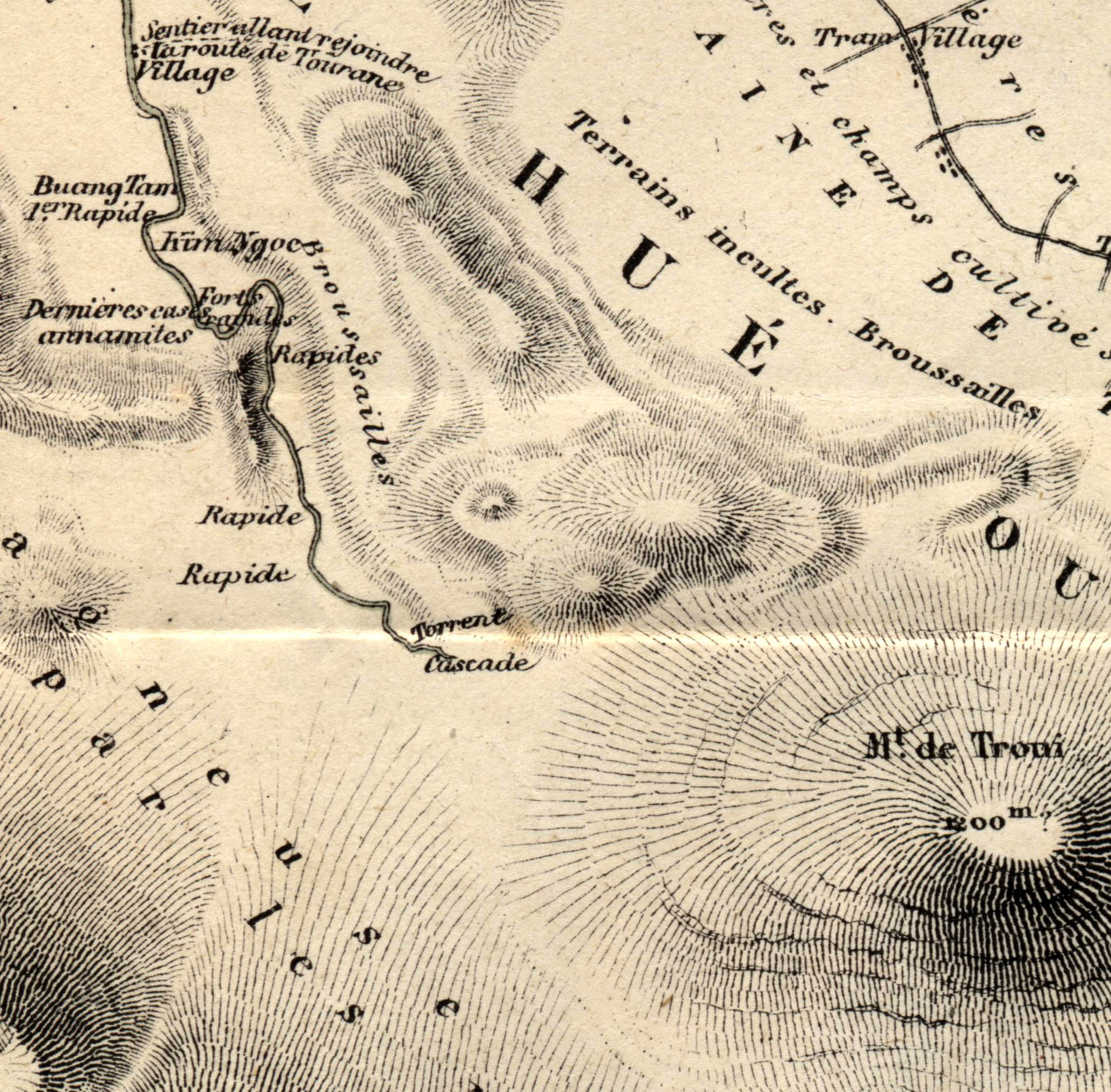

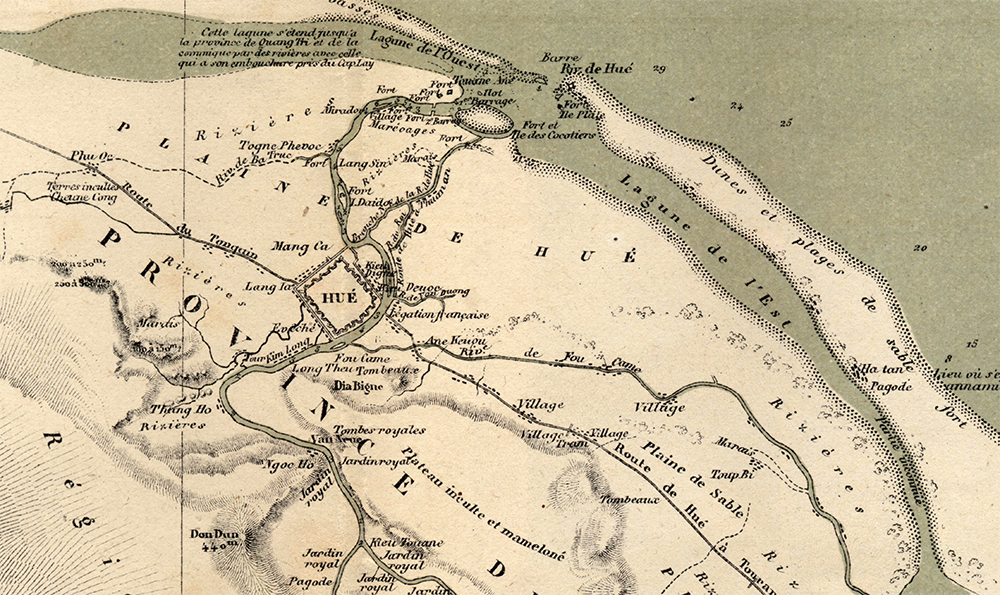

When I pulled an original copy of Detreuil du Rhin’s book, I found these two map gems in the back. They represent one of the earliest public maps available to French reading audiences curious about this far-off kingdom that had recently ceded an area the size of France to Emperor Louis Napoleon in 1867. I discuss the survey mission in detail in my book, Footprints of War, (pp. 41-45) because such mapmaking played an outsized role in shaping French colonial ambitions about the potential productivity of these newly claimed lands. As one might expect, adventurers had a tendency to both minimize the challenge of dealing with unruly natives and maximizing the potential for unclaimed, uncultivated lands to yield profits on valuable industrial or export crops.

Writes Dutreuil du Rhins of the people living around Huế:

More than half of the arable land in the province of Hue is still uncultivated, due to different causes that we have already spoken, mainly the laziness of the Annamese [Vietnamese] and their pitiful government. … The Annamite, for whom foreign trade is prohibited, has no interest in the rich crops which would cost him too much fatigue, and it is not encouraged to produce cereals beyond the needs of his consumption because the mandarins, cowardly and crawling with their superiors and as hard and rapacious with their inferiors, they soon despoil his reserves. Le R oyaume d’Annam et les Annamites, 282-3.

If this kind of insulting-yet-purposeful language wasn’t enough, Detreuil du Rhin’s maps visually advanced this point by visually presenting what were deeply eroded, red-clay ravines carving the hills above Huế as gently sloping hills, allegedly still covered in a layer of topsoil, sure to nourish verdant crops of corn, tobacco, or jute. Meanwhile common features in maps of the day such as village names, fields and cemeteries were almost wholly erased. The following excerpt from the Carte de Hue (full-res version) in multiple senses covered over these facts-on-the-ground and for specific purposes. They provided would-be French readers-turned-colonizers an image of a place where they might pursue their fortunes in these greener, gently sloping pastures. Dutreuil du Rhons was, like many adventurer-cartographers of his day, was like a 19th century real estate agent, shaping both the state’s and the public’s ideas of what such far-off places as Annam might be like.