Thanks to support from the University of Washington’s Center for Southeast Asia and its Diasporas, I finally paid a visit to a place I have long read about and dreamed of: Yogyakarta!

UCR colleague Muhamad Ali and his lovely wife Dila helped me network via their family in Jogja who introduced me to the amazing Kemuning A. Adiputri, who worked with me for a few days as expert guide not only familiar with historic sites around Yogyakarta but actively involved with Stuppa Indonesia, a planning and development firm in Jogja, and the Center for Heritage Conservation (CHC) at Gadjah Mada University. Kemuning recently finished her M.Sc. in Historic Preservation from Columbia University, so I was not just lucky to have a great interpreter but really lucky to meet a future leader in Indonesia’s heritage conservation community!

My main purpose in the Jogja trip was relatively simple: to visit and experience firsthand sites I have long lectured on in my Early SE Asia survey course and to photograph them for a textbook I am writing for Cambridge Press titled An Environmental History of SE Asia. Besides visiting Jogja I made trips to the world’s largest Buddhist monument, Borubudur built in the 9th century CE, and the Hindu temples at Prambanan, also 9th century. We had the great good fortune to see Borubudur on a clear day with full views of the eight mountains surrounding the monument on all sides.

The artistry in the bas-relief carvings along the walls of both monuments is incredible. Here is a detail of three women standing in front of what looks to be a mango tree.

Both Borubudur and Prambanan are built from andesite, a blue-gray volcanic rock. This produced a striking, dark temple which absorbs more heat and which I imagine was likely painted when the temple was in use. Here’s a detail along an outer wall of a monkey with an ox and some mango trees in the background.

Here are some views at Prambanan.

My general interest in both public and scholarly research these days follows from an intro I wrote to a special issue with the Journal of SE Asian Studies three years ago: “The Greening of SE Asian History.” For so long, SE Asia’s history has been defined by issues of state formation and ethnonational heritage-making, what Ben Anderson provocatively termed the making of “imagined communities.” This “national idea” has been vital to different publics in Southeast Asia since the end of colonial rule and the start of decolonization in 1945, but with greater economic integration and global problems like climate change, I think we’re at a turning point for historians, what historian John Smail called an “historiographical crisis” — in SE Asia and the world — where the nation-state project and more recent post-structuralist debates in the academy are giving way to more “diasporic,” trans-regional and even “multi-species” projects exploring new identity-making projects and forging newer historical and analytical framings. SE Asia’s incredible and biodiverse natures, layered cultural landscapes, agro-ecologies – not to mention so many pockets of its endemic, minority or hybrid cultures – are still absent in anglophone histories of the region and marginal in the region’s national museums and vernacular literatures.

This isn’t unique to SE Asia, either — consider the visibility of African Americans or Native Americans in American history books or the decades-long struggles to build a National Museum of African American History on the National Mall – a monumental space largely built in the 19th century by the hands of free and enslaved African Americans. But the times, they are a changin’… and that’s why I open my intro essay with these lines from Bob Dylan:

Hey, hey Woody Guthrie, I wrote you a song

‘Bout a funny ol’ world that’s a-comin’ along

Seems sick and it’s hungry, it’s tired and it’s torn

It looks like it’s a-dyin’ and it’s hardly been born

(Bob Dylan, ‘Song to Woody’, recorded 20–22 Nov. 1961)

I think the newspapers and end-times people would have us believe we’re at the precipice of a world ending in chaos, but who are we to judge? 🙂 Scientists globally tell us we’re at least on the verge of a new, warmer world with all of the possibilities and problems that will pose. A sixth mass extinction, mass die-offs of coral, losing much of the world’s biomass of insects, possibly a plethora of micro-organisms and algae species we don’t even know yet. We’re also in the midst of a mass extinction of thousands of endangered languages. But what about history, especially local history and the history of worlds past? Worlds with more biodiverse forests, more languages, and more natural wonders like the giant stinky flower, Rafflesia arnoldii.

There are efforts in many parts of the world, in the face of climate change and recent social movements for more inclusive histories, inclusive of different peoples and natures, to articulate new valuations of nature/ecosystem services, and combined bio- and cultural diversity to effect a kind of green ethics. I discuss this in my intro to the special edition. These efforts at “greening history” are dispersed globally and draw from multiple groundings in different ethical and religious traditions. What particular natures or landscapes mean to the human communities that tend them are (and should be) as biodiverse as the diversity of life itself. That…in a (Canarium) nut shell is my general research aim in current and developing projects.

The Jogja trip was mostly for fun, photographing sites for teaching and my current book project, but through conversations with Kemuning and a chance trip to an orchid nursery halfway up Mt Merapi, I stumbled onto two related ideas/questions that might bear research fruit down the way.

Cultural- and Bio-diversity at Yogyakarta’s “Cosmological Axis”

Kemuning shared about one of her current projects – supporting heritage conservation in the historic, sacred center of Yogyakarta, including its famed keraton (royal palace) and the street running north from the palace to the central rail depot. Tourists know this 24-hour, busy shopping street as Malioboro Street, and it is adorned with ornate lamp posts and a mosaic of shopfronts from different eras.

The name Malioboro is a bit of a mystery. Some say that it stuck after “Sir” Thomas Stamford Raffles’ ordered British forces to attack the palace in 1812 and loot its precious objects and documents. Malioboro could be the local pronunciation for the name Marlborough, as in the Duke of Marlborough (who was at the time George Spencer-Churchill, a famed collector of antiquities in the UK who was allegedly deeply in debt.) Or it might have referred to an earlier Marlborough who was a governor and the namesake for a British fort at Bengkulu in Sumatra. Or it might derive from a sankritic term, malya bhara, meaning bearing garlands. Just this year, The Cosmological Axis of Yogyakarta and its Historic Landmarks were listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

It now fits within a class or urban historic districts including the Georgetown District in Penang which I also visited on this trip (a separate Reflection blog will cover that). As Georgetown-Penang’s Director Ang told me last week, one of the biggest challenges with maintaining an historic district and a buildings-focused approach is attracting new generations of visitors. The bulk of visitors and community members to these districts are people over 40. No youth!

What some urban districts are doing, and Director Ang is at the forefront, is to place more focus on the living city, arts inside old buildings, new venues for creative expression, and adaptive reuse of old buildings. In New York, there are also efforts to focus on indigenous spaces, place names, plants, and other sites partially buried under concrete. Other conservation projects focus on re-opening creeks from old, concrete storm drains so as to allow migratory birds and other life to return. Seoul is famous for Cheonggyecheon Creek Project, and re-opening it allowed a new shopping district to form along the banks with native and historic trees planted. My hometown of Riverside is similarly planting xeriscape and native sage-scrub in revitalized historic areas with recently restored Japanese American homes, its bid to advance its “arts and culture” mission.

Thinking about these issues in Jogja, two things I noticed immediately were the incredible kampong (alleyway neighborhoods) running off the main streets and the city’s immense banyan trees which are described beautifully by John Ryan in his new work The Mind of Plants!

Here are some shots of one Kampong near the city center at its Tugu Yogya monument:

What’s clear from the many architectural styles, the signs, the placement of art personal and communal with plants and other decor … is that this kampong is well organized by community leadership with strong collective participation in neighborhood life! This is rare in many historic districts where working class people are forced out by high rents and tourist industries and tourists move in. Just blocks off the tourist corridor on Malioboro Street local neighborhoods are still full of everyday, working-people life with beautifully decorated murals around a thriving elementary school, meaning young people, too. That’s a good sign!

Compare this with other historic districts like downtown Amsterdam and you do not see this to the same degree. The streets and pristine historic buildings there are mostly air bnb’s and homes for the global wealthy or inhabited by elderly people who inherited or bought flats in them long ago when they cost normal prices. New York City just passed an ordinance eliminating 67% of its airbnb’s in an effort to hold on to fast-shrinking, “permanent inhabitant” communities.

In Vietnam where I have worked off and on for thirty years, similar waves of vernacular erasure have taken place as the country’s economy, especially in its old cities, has boomed. Over the years I watched as national and city governments moved quickly to erase all forms of outdated transport like cyclos, graffiti, and “slums.” Old cities like Saigon mushroomed into megacities with a dozen new districts after a long, postwar-induced sleep. Saigon used to be full of scenes like this:

But now, Vietnamese in the urban core who are well off and generally older–average age notching up into the 30s—they have lost this part of the urban fabric of everyday life. They think with nostalgia to the cyclos (pedicabs), the food carts, noodle sellers, and stilt houses from their childhood in the city center.

Bookshops now carry models kids can make of bicycle repair stands, stilt houses, cyclos and noodle shops! But the streets are mostly empty of them.

Malioboro still has plenty of examples of vernacular everyday life and I hope preservationists can find ways to include it along with repurposed mid-century “national” buildings, Javanese traditional construction, etc. as things “develop.”

Back to nature in the city, I am amazed by Jogja’s incredible beringin or banyans.

I think Jogja National Museum’s banyan (nighttime pic) should win the blue ribbon, but there are so many to choose from.

Banyans are planted at sites of worship or reverence, and a quick glance at them shows that the tree is not just a single plant organism but a microcosm! Many other life forms live among it including this swallow (Artamus leucorynchus) and so many epiphytes!

(Image courtesy of Wiki Commons and JJ Harrison)

And here is where I imagined some future effort to present the natural heritage in the urban forest might center around banyans, perhaps even some combined presentation of banyans and some of Java’s most famous epiphytes, its native orchids! The city’s banyans might provide unique sites for education about multi-species plant communities. They could even host orchids in outdoor exhibit spaces. A quick run through Singapore’s Changi airport and it’s commercial-garden “The Jewel” should be enough to convince funders there’s a market for orchid gardens and orchid interpretive sites in heavily trafficked, commercial areas .

Along Malioboro Street, orchids are already part of the urban garden, present on many alleys and front porches.

Clearly people and neighborhood governments love banyans and orchids! Examining their multi-species communities, surveying native and cultivated, imported life, thinking of them as sites for digital or mixed media interpretation would make for a wonderful exhibit. Trees like banyans as urban sites for interpretation can be fixed with digital or QR codes and tied to urban heritage projects.

Orchids attract high-rolling sponsors, too, and hybrid cultivars (like tulips and roses) might be named after VIPs. Recently the Netherlands Queen Maxima visited Gadjah Mada University to attend the announcement of a newly cultivated variety of Mt Merapi’s celebrated species, Vanda tricolor such that it was named Vanda tricolor “Queen Maxima.” If royals are into orchids, there seems a ready source for investment into interpretation.

My hometown, Riverside CA, used an app for school kids and amateur birders to photo and geotag pics to a naturalist website showing sightings of birds. Unfortunately, plants cannot fly, so geotagging them opens up the same problems it does for ancient remains: poachers! Anyway, there are ways to safeguard locations and still present digital images for a sort of citizen science. And Vanda tricolor is but one of hundreds of Mt. Merapi area species – the one most cultivated by commercial nurseries.

Merapi Orchids

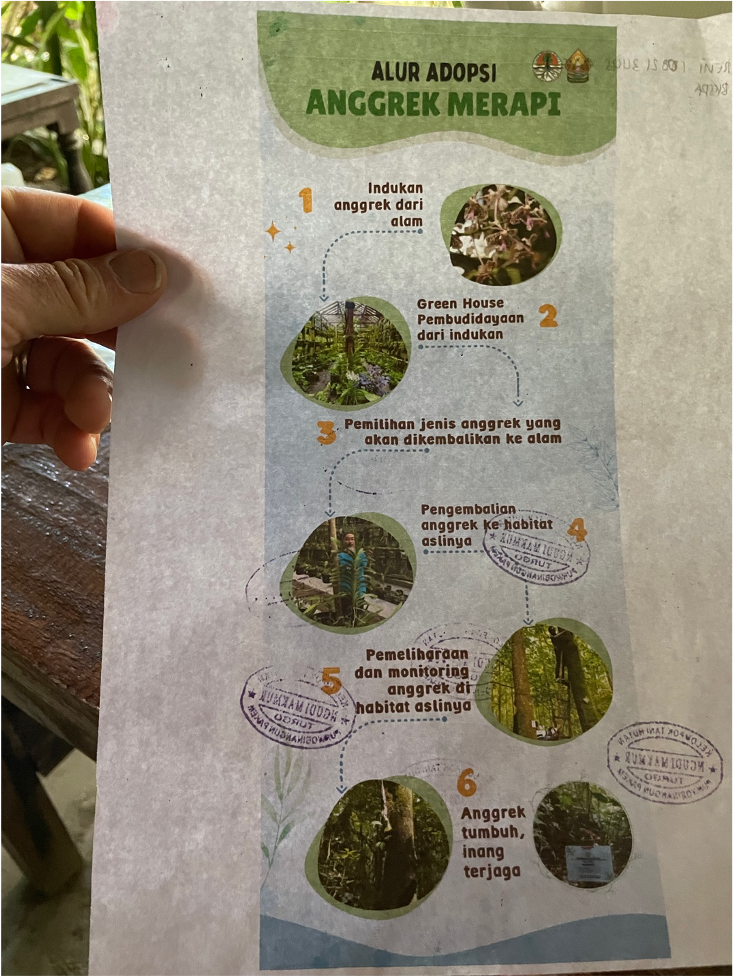

Holding the banyans idea for a sec, let me explain how I stumbled on orchids as one focus for preservation here. Our Day 2 tour to Borobudur was delayed by requirements for timed entry, so we took a detour to Pak Musimin’s orchid conservation nursery on the southern slope of Mt Merapi.

This is a conservation center propagating and re-establishing orchids in Merapi’s forests. Pak Musimin explained how native orchid habitats are under threat from forestry, natural destruction from eruptions and orchid-poaching. For twenty years, he and his wife have worked with Yogya orchid conservation groups to adopt orchids and then, when mature, re-establish them in forest habitats. They even developed a program for city people to adopt them and, once mature, return them to re-establish in the forest.

Mindblowingly cool!!!!! The idea of bringing in an urban community of orchid adopters which builds immediate and deep ties between cityfolk and a specific species and site in the forest. This, I think, is a brilliant strategy for promoting sustainable biodiversity conservation in the city.

On Malioboro Street one could incorporate biodiversity into historic preservation programs. I think the banyans and their human communities might serve as interesting sites for interpretation about native orchids , especially the globally popular (Mt Merapi native) Vanda tricolor.

(image courtesy of Judy Carney)

Perhaps kampong communities connected with banyan trees could participate in orchid adoption, even naming them, and build interpretive panels for visitors on orchid-banyan tours. Protected banyans inside private grounds like mosques and historic sites might try establishing Vanda tricolor — assuming the plant can adapt to these urban trees.

Why are orchids important to history?? Culturally they have been important in Asia for more than 2000 years. There are orchids are found carved in stone at Borubudur and Prambanan, two 9th century monuments. The cut flowers keep for a long time, and they were used by traditional dancers, and the plants are biologically incredible. The can reproduce sexually (seed) and asexually (dividing at roots), they attract bats, birds, bees, other insects, even flies, as pollinators. And they symbolize healthy rhizomal, mycorrhizal communities. There is so much research right now in the roles of fungal communities in rehabilitating forests…and cities! Along with algae and other micro life forms.

So the symbol of Yogya’s official plant on Yogya’s historic banyans…it could serve as an important focal point for studying both the city’s and surrounding area’s multispecies community of life.

One of my favorite anthropological theorists for her multispecies approach is Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing who was trained as a specialist of Indonesia and wrote award-winning books like In the Realm of the Diamond Queen and Friction detailing field experiences in Kalimantan with Dayak peoples and connecting them to more global flows of people and natural products, commerce. I think her work might help to theoretically inform a preservationist project aroung Jogja and Merapi, especially her more recent books including The Mushroom at the End of the World and her collaborative, open-access work Feral Atlas.

Orchids are not only a huge business all over Asia and the Pacific (esp. Hawaii) but their native range matches well with the arc of Indo-Pacific countries connected to the historic Austronesian migration. All across the region stretching from Madagascar to Easter Island are orchid hotspots.

Hawaii’s orchid business is so developed that nurseries sell tourists flowers already packed and certified “clean” to pass border and customs requirements. Like tulips in Holland, they are ready for carry-on!

Perhaps there is an angle with orchids to connect the diverse island peoples and island ecologies where orchids originate, like Merapi’s pockets of diversity high up the slopes, in between lava stone and lahar. There should be possibilities for Yogya-area nurseries to profit from the export of its indigenous biodiversity.

I gather from academic papers in English that Gadjah Mada University’s plant scientists are leaders in the study of Merapi’s orchids, and I imagine there are plenty of experts who could help design orchid conservation, adoption, conservation and sales. I of course have none, just a regional historian’s eye for comparisons and metaphors–perhaps a resource for global or trans-regional comparisons. But to collaborate on such a project would be a delight!!!!

A newcomer’s fascination with Yogya! 🙂

I’m returning to Riverside for a busy quarter of teaching, including a trial course on modern se asian history through the lens of historic plants — teak, abaca, rubber, pepper, sugar, etc. But next spring I will start a long-planned Fulbright Fellowship at Universiti Sains Malaysia, so possibly from there I can explore this orchid idea…along with a mangrove one, and no doubt others.

Terimah kasi!!!!

I owe my deepest thanks to the friends and family in Yogya who shared their time and their Yogya lives with me. Thanks to Dila’s parents and sisters for a delightful Saturday night dinner with amazing sweet treats.

Yogya people have an incredible sense for sweet and varied desserts!!!! Dila’s sister scored a new top hit – a dish with melon, lime, ice and coconut!!!! Me and my extra kilo thank you!

Thanks to driver Yusuf and his niece and interpreter Eggy who joined me for a hilariously fun trip to explore the southern coast of Java, its historic sites and national parks. They also shared about their life in a kampong on the edge of Yogya, about his experiences working in West Java’s steel mills, her experience going to college, working in call centers, and their work in the kampong preserving rich artistic traditions, also on raising kids, hoping for marriage, and many other things — sometimes hilariously mis/translated by Google Translate!

Through my colleague and dear friend, former Fulbright Visiting Prof at Riverside, Baskara Wardaya SJ, I was able to visit his community and learn about his research including a wonderful new book titled Awan Merah (Red Cloud) — that includes his observations from extensive travels in America, including a recent stay in Riverside!

Finally, sincere thanks to Kemuning Adiputri for taking time from her professional work, friends and family for two days of intense touring, long car rides and answering hours of my nonstop questions, helping me learn from local experts and being perfectly brilliant! I felt not that I was talking with a recent graduate but a colleague with decades of observations and life experiences. Best wishes to your family, many thanks, and I look forward to meeting in the future!

To all Yogya friends: I look forward to when you will visit me in California! You have a friend in Riverside, and if baseball season is happening, plan on a trip to Dodger Stadium’s Top Deck! 🙂 Like here with Ali, Dila, Tam, Linh and their kids!